|

|

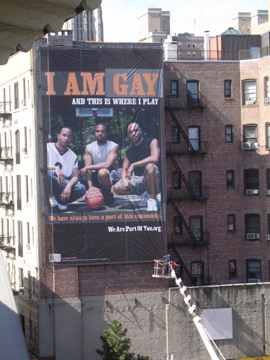

| Campaign for Black Gay Men's Lives. |

| CONTINUE THE TOUR |

|

GLBTQ RACISM: A Time to Address our Secret.

A Different Shade of Queer: Race, Sexuality,

and Marginalizing by the MarginalizedShared experiences of oppression rarely lead to sympathy for others who are

also marginalized, traumatized, and minimized by the dominant society. Rather, all too miserably, those who should naturally

join in fighting discrimination find it more comforting to join their oppressors in oppressing others. As a gay man of color,

I see this on a routine basis – whether it be racism in the gay community or homophobia in communities of color.Chong-suk

Han

By now, two things are bitterly clear about our “shared” American experiences. One, a shared history of

oppression rarely leads to coalition building among those who have been systematically denied their rights. More devastatingly,

such shared experiences of oppression rarely lead to sympathy for others who are also marginalized, traumatized, and minimized

by the dominant society. Rather, all too miserably, those who should naturally join in fighting discrimination find it more

comforting to join their oppressors in oppressing others. As a gay man of color, I see this on a routine basis – whether

it be racism in the gay community or homophobia in communities of color. And it pisses me off. I’m sure, about why such things happen. But for now, I’m

not interested in why it happens. Rather, I’m interested in exposing it, condemning it, shaming it, and stopping it.

Many gay activists want to believe that there

aren’t issues of racism within the gay community. As members of an oppressed group, they like to think that they are

above oppressing others. Yet, looking around any gayborhood, something becomes blatantly clear to those of us on the outside

looking in. Within the queer spaces that have sprung up in once neglected and forgotten neighborhoods, inside the slick new

storefronts and trendy restaurants, and on magazine covers, gay America has given a whole new meaning to the term “whitewash.” Whiteness in the gay community is everywhere,

from what we see, what we experience, and more importantly, what we desire. Media images now popular in television and film

such as Will and Grace, My Best Friend’s Wedding, In and Out, Queer as Folks, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, The L-Word,

etc. promote a monolithic image of the “gay community” as being overwhelmingly upper-middle class – if not

simply rich – and white. Even the most perfunctory glance through gay publications exposes the paucity of non-white

gay images. It’s almost as if no gay men or women of color exist outside of fantasy cruises to Jamaica, Puerto Rico,

or the “Orient.” And even there, we apparently only exist to serve the needs of the largely gay white population

seeking an “authentic” experience of some kind. To the larger gay community, our existence, as gay men and women

of color, is merely a footnote, an inconvenient fact that is addressed in the most insignificant and patronizing way. Sometime

between Stonewall and Will and Grace, gay leaders, along with the gay press, have decided that the best way to be accepted

was to mimic upper middle-class white America. Sometimes, racism in the gay community takes on a more explicit form aimed at excluding men and women

of color from gay institutions. All over the country, gay people of color are routinely asked for multiple forms of I.D. to

enter the most basic of gay premises, the gay bars. In the 1980s, the Association of Lesbian and Gay Asians found that multiple

carding was widespread throughout the city of San Francisco and the “Boston Bar Study” conducted by Men of All

Colors Together Boston (MACTB) cited numerous examples of discrimination at gay bars against black men. Rather than a specter

of gay whitening practices from the past, the efforts to exclude gay men of color are still in full swing. In 2005, the San

Francisco Human Rights Commission found that the San Francisco BadLands, a once popular bar, violated the civil rights of

non-white patrons and employees by denying entrance to, and employment at, the bar. Denied access to the gay bars, gay men

and women of color often lose the ability to see and socialize with others “like them” who also turn to these

“safe” places for not only their social aspects but their affirming aspects. Isolated incidents might be easily

forgotten, but news reports and buzz on various on-line forums expose such practices to be endemic to gay communities. More importantly, gay men and women of color

are routinely denied leadership roles in “gay” organizations that purport to speak for “all of us.”

In a process that Allan Bérubé calls “mirroring,” gay organizations come to “mirror” mainstream organizations

where leadership roles are routinely reserved for white men and a few white women. As such, it is the needs and concerns of

a largely middle class gay white community that come to the forefront of what is thought to be a “gay” cause.

Interjecting race at these community organizations is no easy task. On too many occasions, gay men and women of color have

been told not to muddy the waters of the “primary” goal by bringing in concerns that might be addressed elsewhere.

When mainstream “gay” organizations actually address issues of race, gay white men and women continue to set the

agenda for what is and is not “appropriate” for discussion. Likewise, when “ethnic” organizations

set the agenda, gay and lesbian issues are nowhere to be found. The primacy of whiteness in the gay community often manifests as internalized

racism. In “No blacks allowed,” Keith Boykin argues that “in a culture that devalues black males and elevates

white males,” black men deal with issues of self-hatred that white men do not. Boykin argues that this racial self-hatred

makes gay black men see other gay black men as unsuitable sexual partners and white males as ultimate sexual partners. hatred. Rather, it seems to be pandemic among

many gay men of color. Even the briefest visit to a gay bar betrays the dirty secret that gay men of color don’t see

each other as potential life partners. Rather, we see each other as competitors for the few white men who might be willing

to date someone “lower” on the racial hierarchy. We spend our energy and time contributing to the dominance of

whiteness while ignoring those who would otherwise be our natural allies. When Asian men tell me that they “just don’t

find Asian guys attractive,” I often wonder what they see when they look in the mirror. How does one reconcile the sexual

repulsion to their race with the reflection in the mirror?

Ironically, we strive for the attention of the very same white men who view

us as nothing more than an inconvenience. “No femmes, no fats, and no Asians,” is a common quote found in many

gay personal ads, both in print and in cyberspace. Gay white men routinely tell us that we are lumped with the very least

of desirable men within the larger gay community. To many of them, we are reduced to no more than one of many “characteristics”

that are considered undesirable. Rather than confronting this racism, many of these gay Asian brothers have become apologists

for this outlandish racist behavior. We damage ourselves by not only allowing it, but actively participating in it. We excuse

their racist behavior because we engage in the same types of behavior. When seeking sexual partners for ourselves, we also

exclude “femmes, fats, and Asians.” We hope that we are somehow the exception that proves the rule. “We’re

not like other Asians,” we tell ourselves. I’m sure that similar thought go on in other minds, only, “Asian”

might be replaced with black, Latino, Native American, etc. In our minds, we are always the exceptions. The rationale we use, largely to fool ourselves,

to justify the inability of seeing each other as potential partners and allies, is laughable at best. Many Asian guys have

told me that dating other Asians would be like “dating [their] brother, father, uncle, etc.” Yet, we never hear

white men argue that dating other white men would be like dating their brothers or fathers. This type of logic grants individuality

to white men while feeding into the racist stereotype that all of “us” are indistinguishable from one another

and therefore easily interchangeable. Some of us rely on tired stereotypes. Boykin writes about the professional gay black man who degrades

other black men as being of a “lower” social class while thinking nothing of dating blue-collar white men. If we are invisible in the dominant gay community,

perhaps we are doubly so in our own communities of color. If we are a footnote in the gay community, we are an endnote in

communities of color – an inconvenient fact that is buried in the back and out of view. We are told, by family and friends,

that “being gay,” is a white “problem.” We are told, early in life, that we must avoid such stigma

at all costs. When we try to interject issues of sexuality, we are told that there is precious little time to waste on “trivial”

needs while we pursue racial justice. I’ve seen those who are marginalized use the master’s tools in numerous instances, now too

legion to list. Citing Leviticus, some people of color who are also members of the clergy have vehemently attacked homosexuality

as an “abomination.” This is the same Leviticus that tells us that wearing cloth woven of two fabrics and eating

pork or shrimp is an “abomination” punishable by death. Yet not surprisingly, rarely do Christian fundamentalists

picket outside of a Gap or a Red Lobster. If hypocrisy has a border, those yielding Leviticus as their weapon of choice must

have crossed it by now. It must be convenient to practice a religion with such disdain that the word of God need only be obeyed

when it reinforces one’s own hatred and bigotry and completely ignored when it is inconvenient. How else do we explain

those who condemn Brokeback Mountain based on their “religious” views while, in the same breath, praise Walk the

Line, a movie about two adulterous country singers? On purely religious views, doesn’t adultery rank higher on the list

of “sins” than homosexuality? After all, adultery is forbidden by the Ten Commandments while homosexuality is

not. More problematic

is that we chose to practice historic amnesia by ignoring the fact that Leviticus was used by slave owners to justify slavery

by arguing that God allowed the owning of slaves and selling of daughters. Anti-miscegenation laws, too, were justified using

the Bible. In 1965, Virginia trial court judge Leon Bazile sentenced an interethnic couple who were married in Washington,

D.C. to a jail term using the Bible as his justification. In his ruling, he wrote, “Almighty God created the races white,

black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. The fact that he separated the races shows that he

did not intend for the races to mix.” Scores of others also used the story of Phinehas, who distinguished himself in

the eyes of God by murdering an inter-racial couple, thereby preventing a “plague” to justify their own bigotry.

Have we forgotten that the genocide and removal of Native Americans was also largely justified on biblical grounds? Have we simply decided to pick and choose the

parts of the Bible that reinforce our own prejudices and use it against others in the exact same way that it has been used

against us? Have we really gotten this adapt at using the master’s tools that he no longer needs to use them himself

to keep us all “in our place”? Given the prevalence of negative racial attitudes in the larger gay community and the homophobia in

communities of color, gay people of color have to begin building our own identities. For gay people of color to be truly accepted

by both the gay community and communities of color, we must form connections with each other first and build strong and lasting

coalitions with each other rather than see each other as being competitors for the attention of potential white partners.

We must begin confronting whiteness where it stands while simultaneously confronting homophobia. More importantly, we must

begin doing this within our own small circle of “gay people of color.” We must confront our own internalized racism

that continues to put gay white people on a pedestal while devaluing other gays and lesbians of color. Certainly, this is

easier said than done. The task at hand seems insurmountable. In Seattle, a group of gay, lesbian, and transgendered social

activists from various communities of color have launched the Queer People of Color Liberation Project. Through a series of

live performances, they plan on telling their own stories to counter the master narratives found within the larger gay community

and within communities of color. Certainly, gay people of color have allies both in the mainstream gay community and in our communities of color. Recently,

Kahlil Hassam, a high school student in Seattle won a national ACLU scholarship for opposing prejudice. Hassam, the only Muslim

student at University Prep High School, decided to fight for justice after a Muslim speaker made derogatory comments about

homosexuals. Despite his own marginalized status as a Muslim American, Hassam confronted the homophobia found within his own

community. Examples such as these are scattered throughout the country. Nonetheless, there is much more that allies, both

straight and gay, can do to promote social justice. We must see “gay rights” and “civil rights” as

being not exclusive but complimentary. All too often, even those on the left view supporting “other” causes as

being more about the Niomoellerian fear of having no one left to speak up for us if the time should come. I propose that the

motivation to join in “other” causes should come not from such fears but from the belief that there are no such

“other” causes. Rather, as Martin Luther King Jr. reminded us, “an injustice anywhere is a threat to justice

everywhere.” We must remind ourselves, contrary to what Cannick may want us to believe, social justice is not a zero-sum

game. Granting “rights” to others do not diminish our rights. Rather, it is the exact opposite. Ensuring that

“rights” are guaranteed to others ensures that they are guaranteed to us.

|